My first introduction to the concept of STEMinism was through The Love Hypothesis by Ali Hazelwood, a neuroscientist and secret fiction author (Hazelwood is her pen name) who writes about women in STEM-related academia. She highlights the challenges and triumphs of women in science, sprinkled in with a bit of dramatization, making for an immensely entertaining read. (I started reading Love on the Brain in a Barnes and Noble in Union Square and did not leave my table by the window for the five hours it took me to finish it). While the plots of her books are somewhat homogenous (a nerdy girl in academia + obscure medical condition – for some odd reason, this is always the case + career struggles), there’s something inexplicably exciting around reading about a female powerhouse neuro engineer working at NASA that make the occasional face-palm worth it.

This genre of books – what I’ll stamp as the STEMinist fiction genre – has taken the literary world by storm. Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus is a #1 New York Times Bestseller that has sold millions of copies worldwide. It is set to become a TV series premiering in October (I fully intend to drop everything to watch). There is something enormously gratifying about the fact that so many people enjoy the witty, nerdy, intense brilliance of Elizabeth Zott enough for it to disseminate so much.

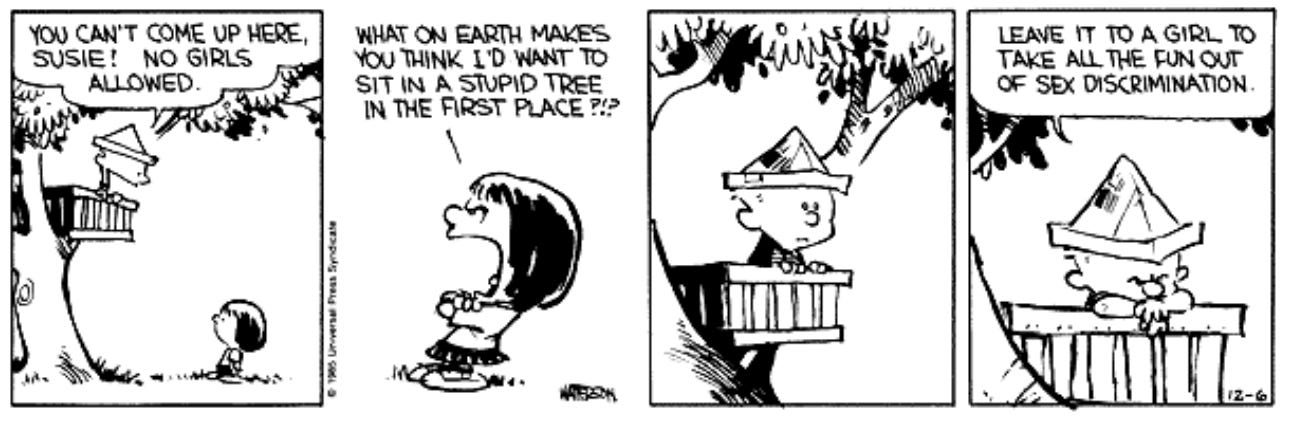

These works are a breath of fresh air from the unvarying stories of all-male research groups: the ones with trophy wives and mistresses who are forgiven because they are just too brilliant to be worth it to smear their legacy. It is validating to see the main character go through all the nonsense that many aspiring female scientists have already begun to get a flavor of. And it is comforting to witness them lead personal and family lives, and yes, struggle to do so.

I happen to think that the biggest challenge we face cannot be strictly ascribed to external factors or blatant sexism. I am somewhat optimistic that these barriers are dwindling in might, that progress is being made, and that recognition is increasingly being attributed to those who deserve it.

This is not to diminish where these challenges remain all too pervasive. Sexism is notably most persistent in academia, where the most established, tenured, and at-the-top professors are more likely to be alike than diverse. Estimates show that progress is a long way to go; our collective job is nowhere near finished.

In my view, the biggest challenge for women – our biggest challenge – is overcoming ourselves. Specifically, the all-too-familiar tendency to underestimate, self-doubt, and diminish. The constant comparison and, frankly, ludicrous standards we impose and enforce. These are not a product of our own wants but conceivably what we are conditioned with. The bar for perfection has always been unattainable.

This is not a difficulty entirely unique to women or girls. Self-doubt is universal; a considerable number of successful people often cite this feeling as one that was all too frequent, particularly in their lowest moments. It has been my observation, and the observation of several experts, however, that our gender experiences these emotions disproportionately.

What first drew my curiosity to this particular issue was my reflections on an immersive competitive science setting. My conversations with female colleagues were markedly different regarding their concerns about the adjudication process. Exchanges were filled with candor about feeling underprepared and behind. During meals between panel judging, it was primarily the women who stayed silent, while others debated and keenly insisted they knew all the answers to the impossible questions presented (no one, in fact, knew all the correct answers). One of my closest friends consistently made semi-serious, self-critical jokes to wish I could have planted in her mind: You are positively brilliant – just believe it!

It is certain that everyone has felt a bit of imposter syndrome and, in this situation, had different ways of expressing it. However, research on gender confidence gaps indicates statistical differences between how we assess our abilities and what they actually are. Women consistently depict their ability and performance as less favorable compared to equally performing men.

Our reaction to these findings has been miserably lackluster. “Take more risks” is preached to the masses. Simply “be more assertive,” and your employers will value you more. When browsing articles on the confidence gap as it relates to women, the first result seems to absurdly suggest that there were fewer female pilots cerca the 1930s just because they were not confident – only Amelia Earhart was daring enough.

These prescriptions miss the point. Exuding more confidence tends to lead to one of two outcomes. In the first, “taking risks” and “being assertive” are occasionally awarded but often punished. Women are accused of overdoing it or overcompensating. In the other situation, the underlying problem is not resolved. Even top female executives who seem to have it all together still admit that they suffer from debilitating confidence issues. Acting a certain way does not necessarily mean you are convinced of your own abilities.

What, then, are more conceivable solutions?

The first place to start is a paradigm shift in how we encourage other women. It is my belief that preaching women to be risk-takers without relating to each other is an infeasible solution. Opening the door to dialogue requires honesty and transparency; one person’s vulnerability can be the spark for empathy ubiquitously.

We also ought to focus earlier on shattering excessively critical mindsets as soon as possible. From my observations, problems with self-critical sentiments are emphasized in the professional sphere yet harbored in young adulthood. Part of the problem for young women, particularly in post-secondary STEM education, is fueled by a lack of visibility and presence of powerful female professors who have the platform and legitimacy to share their stories.

In some ways, this cycle is self-inforcing, hence why it is difficult to absolve these challenges. But women have heard enough of the generic “believe in yourself” to the point where these statements have become void of true meaning. It is time we be honest with each other as early as possible. Only then can we ensure our experiences can be used to genuinely uplift rather than superficially pronounce.